Introduction#

Sample Spaces and Events#

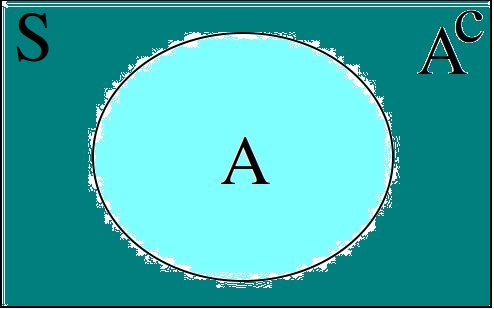

The end goal of each of these problems is to end up with a (universal) set S that describes every outcome in a sample space. The process will be to assign label to outcomes and then collect them into a set.

Let h represent a single coin flip landing on heads. Let t represent a single coin flip landing on tails.

TODO

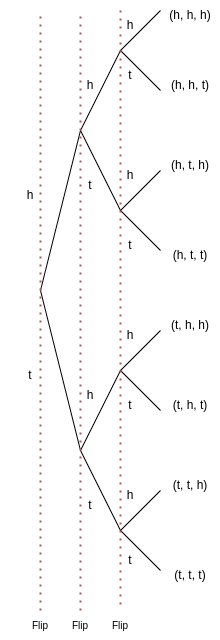

Let h represent a single coin flip landing on heads. Let t represent a single coin flip landing on tails. A tree diagram is useful for visualizing the sample space here,

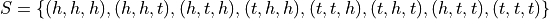

Each outcome in the sample space is an ordered pair of the individual outcomes. Collecting the endpoints of the diagram into a set,

Representing each outcome as an ordered pair is a matter of preference. An equivalent way of formulating this sample space would be,

Here the sequence xyz is written so that x, y and z can take on the values h and t only. In this case, the sample space encodes the exact same information as the previous representation.

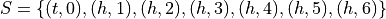

Let 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 represent rolling a die with that number of dots. Then,

Construct a table where the first column represents the outcome of the first die and the first row represents the outcome of the second die. Fill in each entry of the table by listing the outcomes as an ordered pair (x, y),

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

1 |

(1, 1) |

(1, 2) |

(1, 3) |

(1, 4) |

(1, 5) |

(1, 6) |

2 |

(2, 1) |

(2, 2) |

(2, 3) |

(2, 4) |

(2, 5) |

(2, 6) |

3 |

(3, 1) |

(3, 2) |

(3, 3) |

(3, 4) |

(3, 5) |

(3, 6) |

4 |

(4, 1) |

(4, 2) |

(4, 3) |

(4, 4) |

(4, 5) |

(4, 6) |

5 |

(5, 1) |

(5, 2) |

(5, 3) |

(5, 4) |

(5, 5) |

(5, 6) |

6 |

(6, 1) |

(6, 6) |

(6, 3) |

(6, 4) |

(6, 5) |

(6, 6) |

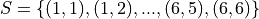

At this point, we could conclude the problem by listing these ordered pairs in List Notation,

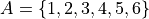

However, this is not entirely satisfactory. If we were presenting this set as a sample of data, we would not be able to use the ellipsis “…”, unless it was understood by the audience how the set of the ordered pairs were being generated, so to prevent miscommunication, we would be required to write out the entire set. However, listing all of these elements (6 rows by 6 columns = 36 entries/elements) can be tedious and time consuming. As an alternative, let us write the same set using Quantifier Notation. To do so, let the set A be ,

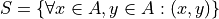

We can quantify over the elements in set A twice to arrive at an alternate solution.

Note

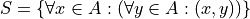

Technically, in the solution, we are using a bit of short-hand. The way it is written there is implicitly two quantification occuring. Selecting all the elements in A through  , and then for each element we have selected, we are selecting each element of A again through

, and then for each element we have selected, we are selecting each element of A again through

If we wanted to be as precise as possible, we should write,

However, this is overly complicated and not very clear; There is nothing gained by adopting this notation. If this were an post-graduate level course in the foundations of set theory, we would be much more careful with how we formulate propositions in our symbolic language. However, we will continue using short-hand when applicable.

A possible representation of this Sample Space is given by,

In this representation the 0 would correspond to not rolling the die at all.

The sample space from #1c will be useful here, so let’s copy it for reference,

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

1 |

(1, 1) |

(1, 2) |

(1, 3) |

(1, 4) |

(1, 5) |

(1, 6) |

2 |

(2, 1) |

(2, 2) |

(2, 3) |

(2, 4) |

(2, 5) |

(2, 6) |

3 |

(3, 1) |

(3, 2) |

(3, 3) |

(3, 4) |

(3, 5) |

(3, 6) |

4 |

(4, 1) |

(4, 2) |

(4, 3) |

(4, 4) |

(4, 5) |

(4, 6) |

5 |

(5, 1) |

(5, 2) |

(5, 3) |

(5, 4) |

(5, 5) |

(5, 6) |

6 |

(6, 1) |

(6, 6) |

(6, 3) |

(6, 4) |

(6, 5) |

(6, 6) |

Table 1

Outcomes of two die rolls.

This problem is asking questions about the sum of outcomes, so let’s rework this table a bit. Instead of entering the outcomes as ordered pairs, we will calculate their sum and enter the result into each entry of the table,

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

Table 2

Sum of two die roll outcomes.

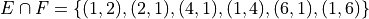

Recall the symbol

correspond to the English “and”.

correspond to the English “and”.  represents the event of rolling atleast one 1 and the sum of the rolls being odd. In other words, we need to look at the outcomes E and F have in common.

represents the event of rolling atleast one 1 and the sum of the rolls being odd. In other words, we need to look at the outcomes E and F have in common.

The outcomes of F, the event of getting at least one 1, are given by the second row and second column of the Table 1 (the row and column with the headings of 1). We can blank out the other rows, since they don’t affect this problem and it will help us keep everythign organized,

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

1 |

(1, 1) |

(1, 2) |

(1, 3) |

(1, 4) |

(1, 5) |

(1, 6) |

2 |

(2, 1) |

|||||

3 |

(3, 1) |

|||||

4 |

(4, 1) |

|||||

5 |

(5, 1) |

|||||

6 |

(6, 1) |

Table 1-1

The outcomes in F.

Similarly, let’s blank out the corresponding entries in Table 2,

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

2 |

3 |

|||||

3 |

4 |

|||||

4 |

5 |

|||||

5 |

6 |

|||||

6 |

7 |

Table 2-1

The sum of two die roll outcomes in F

Now, we need the outcomes that correspond to event E. These are the outcomes whose sum is odd. Removing those entries from the table we get,

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

1 |

(1, 2) |

(1, 4) |

(1, 6) |

|||

2 |

(2, 1) |

|||||

3 |

||||||

4 |

(4, 1) |

|||||

5 |

||||||

6 |

(6, 1) |

Table 1-2

Outcomes in

The corresponding sum of these outcomes is given in the next table,

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

|||

2 |

3 |

|||||

3 |

||||||

4 |

5 |

|||||

5 |

||||||

6 |

7 |

Table 2-2

Sum of outcomes in  .

.

Looking at the second table for outcomes in this column and row that also have a sum that is odd (event E), we see the sums that correspond to this event are 3, 5 and 7.

In other words, the only sums that are odd if at least one of the die lands on 1 are 3, 5 or 7.

To say the same thing in a different way, if the sum of two die rolls is odd, then the only way to get a 1 is if the sum is 3, 5 or 7.

We collect the ordered pairs that correspond to these sums into a set to complete the problem,

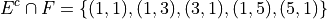

Recall the operation of complementation corresponds to the English word “not”, i.e. the complement of a set is its negation.

If a number is not odd, then it is even. Therefore, the set  is the set of outcomes whose sum is even.

is the set of outcomes whose sum is even.

Thus, the intersection we desire  is the set of even sums that have atleast one 1.

is the set of even sums that have atleast one 1.

Using a similar method to part a, we take Table 2a-1 and remove the outcomes that odd to find the outcomes in the event  ,

,

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

1 |

2 |

4 |

6 |

|||

2 |

||||||

3 |

4 |

|||||

4 |

||||||

5 |

6 |

|||||

6 |

Table 1-3

The even sums with at least one a, i.e.

Using this table, we conclude the desired set is given by,

The question requires the complement of F. Recall from the Aristotle’s Square of Opposition, the complement of getting at least one 1 is getting no 1’s, i.e. the negation of “some are” is “none are”. Therefore,

represents the event of getting no 1’s.

represents the event of getting no 1’s.

The intersection  thus represents the event of getting an even sum that has no 1’s.

thus represents the event of getting an even sum that has no 1’s.

To find the outcomes in the event, first find F^c (it doesn’t actually matter which event/set you start with, just pick one and go with it)

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

1 |

||||||

2 |

(2, 2) |

(2, 3) |

(2, 4) |

(2, 5) |

(2, 6) |

|

3 |

(3, 2) |

(3, 3) |

(3, 4) |

(3, 5) |

(3, 6) |

|

4 |

(4, 2) |

(4, 3) |

(4, 4) |

(4, 5) |

(4, 6) |

|

5 |

(5, 2) |

(5, 3) |

(5, 4) |

(5, 5) |

(5, 6) |

|

6 |

(6, 6) |

(6, 3) |

(6, 4) |

(6, 5) |

(6, 6) |

Table 1-4

The outcomes with no 1’s,

We want to intersect this event with the event of getting an even sum,  . Thus, we remove entries with a odd sum,

. Thus, we remove entries with a odd sum,

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

1 |

||||||

2 |

(2, 2) |

(2, 4) |

(2, 6) |

|||

3 |

(3, 3) |

(3, 5) |

||||

4 |

(4, 2) |

(4, 4) |

(4, 6) |

|||

5 |

(5, 3) |

(5, 5) |

||||

6 |

(6, 6) |

(6, 4) |

(6, 6) |

Table 1-5

The outcomes with no 1’s that have even sums,

The desired set is found by collecting the remaining ordered pairs,

Recall the symbol

correspond to the English word “or”. This problem is therefore asking for the outcomes in the event of getting an odd sum or getting atleast one 1.

correspond to the English word “or”. This problem is therefore asking for the outcomes in the event of getting an odd sum or getting atleast one 1.

To find the set  , use the method from the previous part, except in this case, blank out entries that don’t satisfy the condition of having odd sum or containing atleast one 1,

, use the method from the previous part, except in this case, blank out entries that don’t satisfy the condition of having odd sum or containing atleast one 1,

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

1 |

(1, 1) |

(1, 2) |

(1, 3) |

(1, 4) |

(1, 5) |

(1, 6) |

2 |

(2, 1) |

(2, 3) |

(2, 5) |

|||

3 |

(3, 1) |

(3, 2) |

(3, 4) |

(3, 6) |

||

4 |

(4, 1) |

(4, 3) |

(4, 5) |

|||

5 |

(5, 1) |

(5, 2) |

(5, 4) |

(5, 6) |

||

6 |

(6, 1) |

(6, 3) |

(6, 5) |

Table 1-6

The outcomes which have an odd sum or have atleast one 1,

Collect these elements into a set to complete the problem,

This event would correspond to the event of getting an odd sum or getting no 1’s.

To find the elements in the sets  , blank out the entries in Table 1 that satisfy the condition of membership,

, blank out the entries in Table 1 that satisfy the condition of membership,

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

1 |

(1, 2) |

(1, 4) |

(1, 6) |

|||

2 |

(2, 1) |

(2, 2) |

(2, 3) |

(2, 4) |

(2, 5) |

(2, 6) |

3 |

(3, 2) |

(3, 3) |

(3, 4) |

(3, 5) |

(3, 6) |

|

4 |

(4, 1) |

(4, 2) |

(4, 3) |

(4, 4) |

(4, 5) |

(4, 6) |

5 |

(5, 2) |

(5, 3) |

(5, 4) |

(5, 5) |

(5, 6) |

|

6 |

(6, 1) |

(6, 6) |

(6, 3) |

(6, 4) |

(6, 5) |

(6, 6) |

Table 1-6

The outcomes which have an odd sum or have no 1’s,

This is easily found by simply enumerating all of the outcomes,

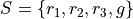

Any time two things are occuring with replacement, it’s a good bet a table would be helpful. Let’s create one like we did in #2, but instead of listing rolls of a die on the headings, let’s use this sample space,

|

|

|

g |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

g |

|

|

|

|

Collect all of these elements into a set to complement the problem,

S = { (r_1, r_1), (r_1, r_2), …, (g, r_3), (g, g) }

When you hear with replacement, think table. When you hear without replacement, think Tree Diagrams. The reason for this is simple. It is very hard (if not impossible) to represent the act of removing an outcome from the sample space in tabular form, whereas it is very natural to represent it with a tree diagram

(INSERT DIAGRAM)

Notice that we lose the element just chosen at each branch of the diagram, i.e. as you move down the tree there is one less branch at each step.

Collecting the endpoints, we can complete the problem,

While this problem is possible by listing the outcomes in the sample space in a set and then finding the events that correspond to A and B in terms of those outcomes and applying the rules of Set Theory, let us try instead to reason it out.

Events are mutually exclusive if they share no outcomes. If the first card has a larger number than the second card, then the second card cannot possibly be larger than the first card. In the other direction, if the second card is larger than the first card, then the first card cannot possibly be larger than the second card. In other words, there is no possible way for A to share any outcomes with B. Therefore, A and B are mutually exclusive by definition.

This part is a bit trickier to see. Recall that the union of complements is equal to the sample space (universal set),

If you take all of the outcomes in an event A and add to them the outcomes not in event A, then you will have all of the outcomes of the sample space.

Then, there are no outcomes outside of the outcomes contained in  plus the outcomes contained in

plus the outcomes contained in  . For, if there were, these two sets would not be complements of one another.

. For, if there were, these two sets would not be complements of one another.

If we can show there is an outcome in the sample space S that does not belong to either  or

or  , then it must follow that A and B are not complements, since their union does not equal the entire sample space.

, then it must follow that A and B are not complements, since their union does not equal the entire sample space.

Consider the outcome of drawing a red card with the number 2 along with a black card with the number 2. In this case, it is neither true that the first card is larger than the second card nor is it true the second card is larger than the first card. Then, there is atleast one outcome in the sample space that belongs to neither of the events. Therefore, we can conclude A and B are not complements of one another.

Classical Definition#

Ah, our old friend. We found the sample of this experiment back in #1 and then examined some events defined on it in #2. Let us copy the results over for quick reference,

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

1 |

(1, 1) |

(1, 2) |

(1, 3) |

(1, 4) |

(1, 5) |

(1, 6) |

2 |

(2, 1) |

(2, 2) |

(2, 3) |

(2, 4) |

(2, 5) |

(2, 6) |

3 |

(3, 1) |

(3, 2) |

(3, 3) |

(3, 4) |

(3, 5) |

(3, 6) |

4 |

(4, 1) |

(4, 2) |

(4, 3) |

(4, 4) |

(4, 5) |

(4, 6) |

5 |

(5, 1) |

(5, 2) |

(5, 3) |

(5, 4) |

(5, 5) |

(5, 6) |

6 |

(6, 1) |

(6, 6) |

(6, 3) |

(6, 4) |

(6, 5) |

(6, 6) |

Table 1 Redux

The outcome of two die rolls

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

Notice the number of elements in the sample space, i.e. its cardinality, is equal to 36, i.e.,

All of the probabilities in this problem can be calculated by crossing out the entries in these tables that do not satisfy the given conditions, counting up the number of entries that remain and then applying the Classical Definition of Probability.

part d and part e are complements. Part d can be rephrased as “at least one of the die is even”. By the Aristotle’s Square of Opposition, the complement of “atleast one” is “none”. This can be verified by summing the probabilities of both events and verifying they add to one,